Set alongside a creek within a shallow canyon of red sandstone, the Pueblo Mission of Abó records a history of inhabitation and colonization that produced the striking ruins of one of only six seventeenth-century Spanish Colonial churches in the present-day United States.

Abó was settled by Tompiro Indians in the 1300s. Their pueblo has not been excavated, but ruin mounds indicate that it had grown by 1600 into a complex of multi-story, L-shaped blocks. Built from the local sandstone, these were clustered around a larger and smaller plaza containing kivas, and housed some 800 people.

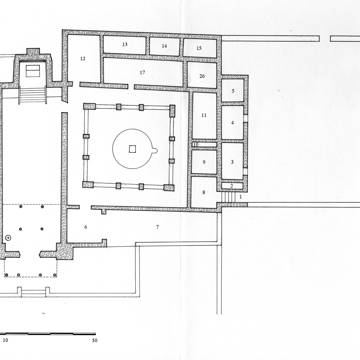

When Fray Francisco Fonte arrived here in 1622, he moved into several rooms in a block at the pueblo’s northeast corner. Altered and expanded, these rooms served as an interim friary ( convento), while Fonte undertook the planning and construction of a permanent mission between 1623 and 1628. Sited further to the northeast, the church and friary of San Gregorio were built facing south toward a cemetery, on a raised platform that compensated for the sloping ground.

The church was a single-nave type without transepts. It measured 25 x 83.5 feet, and had 3-foot-thick walls of sandstone that rose 28 feet to the nave parapets. The facade, with a central door and window between corner buttress towers, was fronted by a wooden porch and balcony that formed a narthex. This led inside to a raised choir loft with a baptismal font in one corner. The nave, with single windows in the middle of both walls, was spanned by squared vigas, spaced two feet apart and supported on corbel brackets. The north, chancel end of the church had a raised high altar in a square apse with lower side altars to either side.

It has been hypothesized that the chancel stood some 10 feet taller than the nave and had a transverse clerestory. The church’s southern—rather than the customary eastern—orientation could have been chosen either to enhance the dramatic light thrown on the chancel from this conjectured clerestory, or to align the church with the pueblo’s south-to-north axis so that it faced towards (rather than away from) the main plaza.

The friary on the east flank of the church was entered through a vestibule porch at its southwest corner. Unusually, its courtyard held a circular kiva. The walkway around the courtyard led both to the sacristy in the northwest corner and to double rows of rooms for the refectory, kitchen, friars’ cells, and storage along the north and east sides.

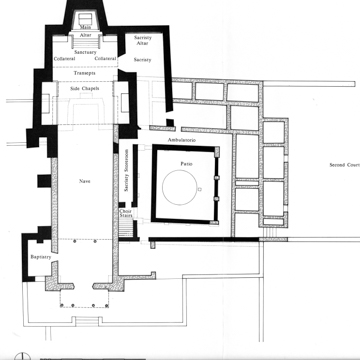

In 1629, Fonte was joined, and then in 1649 replaced, by Fray Francisco Acevedo, who remained Abó’s guardian until 1659. Between 1645 and 1652, Acevedo undertook an ambitious expansion of San Gregorio that kept the original nave walls but otherwise completely rebuilt the earlier structure. The church now extended 132 feet, was widened to 32 feet at the transepts, and climbed to nearly 50 feet on the outside.

A separate baptistery was added at the southwest corner of the facade. The west nave wall was reinforced with buttresses, and the original nave windows were filled in and replaced by a single large window in the east wall. The nave roof was raised and rebuilt with paired square vigas resting on stepped pairs of corbel brackets; the roof parapets were capped with crenellations. The north end was demolished for a completely new sanctuary, with side chapels forming transepts, a transverse clerestory, and a deep chancel with lower side altars and a raised high altar in a trapezoidal apse. A wooden gallery crossed the nave beneath the transverse clerestory, connecting transept balconies while also providing access to a bell tower in the west transept. As George Kubler observed, this transformation at once brought San Gregorio closer to its presumed models of Mexican fortress churches and Il Gesù in Rome, and gave to the interior a sophisticated rhythm of advancing and receding masses.

Concurrently, Acevedo remodeled the friary to accommodate a new and enlarged church sacristy; the kiva might have been partly dismantled and filled in at the same time. This led, by circa 1658, to a more extensive renovation, with a rebuilt porch and a new wing of four friars’ cells and adjoining study alcoves, along a long hallway that ran off the walkway down the entire south length of the friary and adjacent corral. This hallway layout is similar to, and was perhaps modeled after, the friary at Quarai.

In 1673, the friary was burned in an Apache attack and, in the midst of drought and famine, the mission and pueblo were abandoned. New Mexicans resettled the site in the first decades of the nineteenth century, when stone and beams from the mission were used to build a fortified ranch. It was abandoned once again, after renewed attacks by the Apache, who burned the church around 1830. Major campaigns of archeological excavation and stabilization were undertaken in 1938–1940 and 1982–1985.

This National Park Services site is open to the public during regularly scheduled seasonal hours.

References

Ivey, James E. “In the Midst of Loneliness”: The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions. Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 15. Santa Fe: National Park Service, 1988.

Kubler, George. The Religious Architecture of New Mexico In the Colonial Period and Since the American Occupation. 1940. Reprint, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1972.

Treib, Marc. Sanctuaries of Spanish New Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.