The Salinas Pueblo Missions of Abó, Gran Quivira, and Quarai were built in the seventeenth century by Franciscan friars newly arrived from Mexico and the native Tompiro and Tiwa peoples who had lived there for centuries. Now haunting ruins in a memorable if desolate land, these missions testify to the monumental ambitions of New Mexico’s Spanish colonizers, and to the cultural and natural disruptions that caused their abandonment in the 1670s.

The Salinas Missions are located in the Salinas or Estancia Basin, the site of an ancient pluvial lake that left numerous salt flats when it evaporated 10,000 years ago. Attracted by the salt, and by springs in the foothills of the mountains and mesas that border the basin to the west and south, Mogollon Indians first settled here around 700 CE. The migration of Ancestral Pueblo Peoples from the Colorado Plateau, after 1100, led by circa 1300 to the construction of multistory stone-and-clay pueblos, in an agricultural society of dry farmers who cultivated drought-resistant corn, beans, and squash.

Expanded or rebuilt in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, these pueblos became important trading centers, with trade occurring with the pueblos farther west along the Rio Grande and the Plains Indians coming from the east. Buffalo hides, meat, shells, and flint were traded for corn, beans, squash, piñon nuts, salt, cotton cloth, and pottery. By the early seventeenth century, as many as 10,000 people were living in the basin, with significant concentrations at the Tompiro pueblos of Abó and Cueloze, and the Tiwa pueblo of Cuarac.

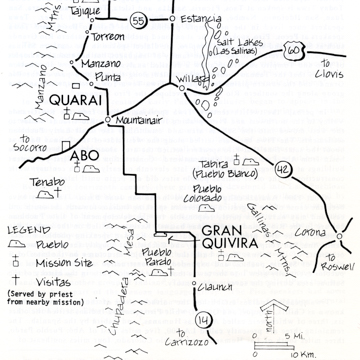

Spanish explorers first stumbled on the Salinas pueblos in 1581–1582. Their colonization began in 1598, when Santa Fe de Nuevo México was established as a province of New Spain and the pueblos were forced to relinquish their sovereignty and accede in an “Act of Obedience and Vassalage” to the Spanish crown. Opposition was met with violent force. Franciscan friars undertook the systematic conversion of the pueblos after the viceroy of New Spain ordered the governor of New Mexico in 1609 to “promote the welfare of these Indians and facilitate their administration.” Directed from the provincial Franciscan headquarters at Santo Domingo Pueblo, missions were founded at Chililí in 1613 or 1614; at Abó in circa 1622; at Cuarac, transliterated phonetically as Quarai, in 1626; and at Cueloze, renamed Las Humanas, in 1629.

From the start, pueblos in the regional jurisdiction of Los Salinas were caught in a struggle for control between the civil administration of the provincial governor and the religious administration of the Franciscan Order. Although both were agents of the Spanish crown, the Franciscans simultaneously answered to the Catholic pope, were exempt from civil law, and had economic interests opposed to those of the provincial government. Where the governor, in return for military service, granted to Spanish colonizers the encomienda, the right to collect a tax of cloth and grain from the pueblos, the friars claimed that their conversion of the Indians, along with the practical instruction they provided in European methods of ranching and farming, gave them the right without payment to a pueblo’s labor and goods. These two forms of civil and religious taxation were in direct competition with each other.

The determination of the Franciscan friars was remarkable. Working alone in villages that numbered from hundreds to several thousand people, their mission was to convince members of that community to abandon their indigenous beliefs and embrace a radically alien religion, in the name of which they were to assist the friar in building a church and adjoining friary ( convento).

To that end, the friars were supplied with a set of tools and finish materials brought from Mexico City: 10 axes, 3 adzes, 10 hoes, 1 saw, 1 chisel, 2 augers, 1 box plane, 10 pounds of iron, a latch and pair of braces for the church door, 12 hinges, 12 hook-and-eye latches, 2 locks, 6,000 nails of various sizes, and a bronze bell. As a practical matter, the friars succeeded because the church and friary duplicated the building technology of the pueblos: walls of local stone laid in clay mortar, and roofs consisting of vigas, latillas, brush, and clay. Masonry work, following Puebloan custom, was by women and children, while men did the carpentry and woodwork.

To these local building methods and skills, the friars brought architectural models from Europe via Mexico. The missions usually faced an enclosed cemetery. The single-nave (hall) churches, without side aisles but often with transepts, ended in either a square or trapezoidal apse. The nave and transepts were spanned with squared vigas set on corbel brackets. The transept beams were often set at right angles and up to six feet higher than those in the nave, creating a transverse clerestory at the end of the nave, which illuminated the sanctuary with natural light. The walls were typically reinforced by facade buttress towers, as well as by additional buttresses on the nave walls and apse. The church facade invariably opened through a double doorway with splayed jambs beneath a large rectangular window, which led inside to a deep choir loft.

George Kubler hypothesized that the buttressed single-nave plan returned directly to the fortress churches of colonial Mexico. He also suggested that the conjunction of a transept clerestory with an aisleless nave and transepts derived ultimately from the sixteenth-century church of Il Gesù in Rome, whose crossing dome was simplified formally into a timber roof structure.

The friary placed alongside the church originated in the cloisters of medieval Europe. It was entered through a vestibule porch ( porteria) and organized around a garth with a courtyard and walkway ( ambulatorio), which led directly or via a hallway to friars’ cells, the refectory, and the kitchen. The corral, a second walled enclosure beyond the friary, contained the stables and storage sheds that supported the agricultural side of the mission.

A circular kiva in the exact center of the friary garth at Abó, and another square one at Quarai, suggest the cultural complexity of these missions. It remains a subject of debate whether these kivas were antecedent to, or contemporary with, the establishment of these missions in the 1620s and 1630s, and therefore whether the inclusion of a Pueblo ritual space in the friary represented an act of suppression, celebrating the victory of Christianity over idolatry, or of syncretism, in which native beliefs were accommodated in a transitional space of conversion.

The success of the friars’ missions depended on reciprocal tolerance from the pueblos. Fray Letrado, founder of the mission at Las Humanas, was killed in 1632 at the Zuni pueblo of Hawikuh after he unwisely called the people to Mass on a festival day; Fray Estévan de Perea, who headed the Holy Office of the Inquisition in New Mexico while stationed at Quarai from 1633 to circa 1639, treated with liberal skepticism most charges of blasphemy, superstition, etc., that were brought to him. Attitudes, however, had hardened by the 1650s and 1660s. At Abô and Quarai, the kivas were partly dismantled and filled in as part of new building campaigns. At Las Humanas, a new church and friary were built without a kiva, while rooms used as kivas inside a nearby housing block indicate that the pueblo was now hiding its religious practices from the Spanish Inquisition.

By the 1660s, the pueblos and their missions were both under stress. Continuing dissension between the civil and religious administrations came to a head when a provincial governor spent the three years of his appointment (1659–1662) relentlessly undermining the friars’ ecclesiastical authority over the pueblos. The Apache Indians became marauding enemies in reaction to Spanish raids that took slaves to work in the mines of northern Mexico, and to the parallel disruption of the Apache’s trading relations with the pueblos. A severe drought exacerbated the destabilizing effects that the introduction of wheat, cattle, sheep, and pigs had on the traditional culture of dry farming. The pueblos were struck by famine after the crops failed in 1667, 1668, and 1669.

The pueblos and their missions were abandoned between 1670 and 1677. Three years later, the reasons for their collapse would prompt many of the surviving pueblos in New Mexico to unite in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and expel the Spanish colonizers—until they returned in 1692.

The pueblo sites remained empty of human inhabitation until New Mexicans began to resettle the Salinas Basin in the first decades of the nineteenth century, only to be driven out by renewed Apache raids around 1830. Slowly ruined by fires, natural decay, and settlers who hauled away stones and beams to use in new structures, the missions were excavated and stabilized in the twentieth century. All three sites were designated National Historic Monuments before they were then combined into the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument in 1980.

The Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument Visitors’ Center in Mountainair is open to the public during regularly scheduled hours.

References

Ivey, James E. “In the Midst of Loneliness”: The Architectural History of the Salina Missions. Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 15. Santa Fe: National Park Service, 1988.

Kubler, George. The Religious Architecture of New Mexico In the Colonial Period and Since the American Occupation. 1940. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1972.

Treib, Marc. Sanctuaries of Spanish New Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Vivian, Gordon. Gran Quivira: Excavations in a 17th-Century Jumano Pueblo. Archeological Research Series No. 8. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1979.