The carnage of the Civil War left the nation with thousands of psychologically shattered and physically maimed men. But since many of them had been volunteers, not career soldiers, they could not seek care in existing military facilities. In 1865, the U.S. Congress passed an act creating a “National Asylum” or “National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.” Thanks to a well-organized local women’s group that had lobbied vigorously for the act, Milwaukee was awarded one of the home’s original three branches. Construction began in 1867. All branches welcomed black as well as white veterans, so that the home was integrated some eighty years before President Harry Truman desegregated the armed forces. In 1871, veterans of conflicts other than the Civil War became eligible. As membership grew, so did the homes. By the 1890s, they included not just barracks, mess halls, and hospitals, but also farm buildings, chapels, shops, libraries, beer halls, theaters, hotels for visitors, and more.

To become a full-fledged community, Milwaukee’s “Old Soldiers Home,” as locals called it, needed a recreation hall, restaurant, post office, and train station. Ward Memorial Hall served these purposes. Although it is only two-and-a-half-stories tall, it is oddly imposing and seems to tower much higher on the main (south) facade because of the gabled central entrance pavilion, which projects from the polygonal bays on either side. A veranda wraps three sides of the building. The playfully colorful brick walls of red stringcourses, red and cream checkerboards in the gables, and red highlights in the window and door arches were all popular treatments in the late Victorian era. A spectacular east-facing stained glass window, installed in 1887, depicts Ulysses S. Grant on horseback.

Inside, Ward Hall—named for a Virginia benefactor—housed several different functions at the ground level and a flat-floor auditorium in the tall second story. In 1895–1897, the auditorium was enlarged and remodeled to accommodate touring theater and vaudeville companies. This auditorium filled the full two and a half stories with a sloping floor, orchestra pit, balcony, and boxes. A rope-and-pin system for flying sets and backdrops was installed behind the stage’s proscenium arch. Plaster columns and cornices, painted blue with gold-leaf embellishments, frame three tiers of boxes, originally reserved for officers and their wives. Above the orchestra seating, the balcony retains its 1897 seats, made of wood, leather, and wrought iron. An ornate design embosses the balcony’s metal underside.

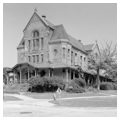

The attractively landscaped veterans’ complex includes other structures dating from the home’s early years, most notably Edward Townsend Mix’s dramatic Main Building (now Building 2), built in 1869 with a looming Gothic tower and multicolored mansard roofs. Today the entire complex is a medical center for the Department of Veterans Affairs.