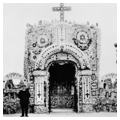

In a formal garden next to Holy Cross Church stands a stunning group of concrete structures encrusted with brightly colored found objects. The Dickeyville Grotto is the most famous and perhaps most magnificent work of outdoor folk art in Wisconsin. It originated in 1919 when German-born Father Wernerus built a conventional Soldiers’ Memorial to three local men who had died in World War I. Then, in 1924, he began to enhance the churchyard’s spiritual and patriotic meaning by constructing a series of religious shrines and monuments.

Assisted by his cousin Mary Wernerus and by George Splinter, the priest sculpted concrete into pedestals, archways, and shrines featuring religious statuary and historical figures. To shape these sculptures, he poured concrete into wooden forms erected atop stone foundations. Altogether, he and his assistants used more than six thousand bags of cement and six or seven carloads of stone. Once the concrete had hardened and the forms were removed, he covered the sculptures with elaborate patterns, using a porous material called petrified moss, along with stones, broken glass, semi-precious gems, tiles, dishware, figurines, and building hardware. Fossils, shells, rose quartz, petrified sequoia and cedar, tufa, stalagmites, and stalactites are among the materials he incorporated into the designs. He achieved some of his most unusual effects with glass. He also used arrowheads, axe heads, and other cultural artifacts that a group of Menominee Indians presented to him.

The most significant structure is the Grotto of the Holy Eucharist, adjacent to the church. A semicircular wall surrounding the structure forms a series of niches containing statues of Christ, the apostles, and St. Joseph. Visitors enter the grotto through a Roman arch, into which three rosaries have been worked. On the rococo interior, precious and semiprecious stones form floral and religious symbols. At the rear the tree of life incorporates petrified wood from South Dakota’s badlands. Along with the gardens, large decorative urns containing glass flowers link the different units and provide unity.

Wernerus’s work was part of a larger Catholic movement to create shrines in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, sparked by celebrated visions of the Virgin Mary at the Lourdes grotto in southern France and by Pope Leo XIII’s replica of that grotto in the Vatican Gardens. Grottos and shrines favored by immigrant Catholics offered accessible settings for personal devotional experience, in contrast to the formal, mediated worship conducted in churches.