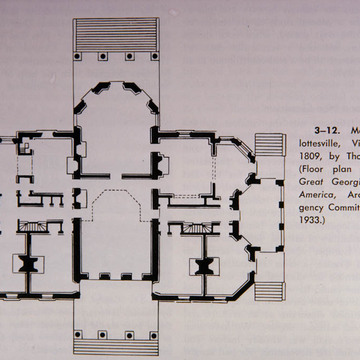

Jefferson was born about four miles east at Shadwell (across the Rivanna River) in 1743. He began contemplating a house on “Little Mountain” in c. 1760, and leveling of the mountaintop began c. 1769. First constructed was the small east pavilion known as the honeymoon cabin. As historians have pointed out, it takes its form and plan from Virginia vernacular buildings. The initial house (how much was built is disputed) was based upon a Palladian formula of a two-story central section, one-story wings, and a basement section (or wings) built into the hillside and then terminated by two small pavilions. In 1793, after his time in France, where he admired the Hotel de Salm, and in England, where he visited Chiswick, Jefferson embarked upon a substantial rebuilding. Although the house was largely complete about 1809, he continued to make alterations until his death in 1826. In a sense Monticello remained under construction throughout Jefferson's lifetime. The problem of incorporating the earlier building can be seen in the second-floor windows, which interrupt the impression of a single-story building that Jefferson wanted to create. Although many specific sources can be pointed out for Monticello, ultimately Jefferson's design far transcends them. It became a personal statement of his taste and its evolution—and an ideal of what Jefferson believed was the appropriate architecture for the young nation. Although its true function is that of a plantation house, architecturally it is much more a villa.

The interior is composed around two large central rooms, the entrance hall, or museum, where Jefferson displayed relics, and the sitting room, or music room. Jefferson's taste in furniture favored a combination of simpler French (Louis XVI) designs, which he imported, and American pieces, some made in Monticello's cabinet shop by slaves. For art, Jefferson collected many copies of Old Masters, a few American works, and busts of famous individuals. In a sense the house was a didactic tool. At the same time, not to be ignored is the submerging of all the servant spaces and, from a post-Freudian point of view, the masking or obliteration of the black slaves who made the running of the house possible. The most memorable interior spaces are his bedroom-library, which takes up most of the first-floor east wing, and the dining room, which, through the use of a dumbwaiter and a turning shelf, made servants invisible.

Jefferson died deeply in debt, and the house passed through several hands before the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation acquired it in 1923. The foundation has carried out an ambitious program of preservation, restoration, reconstruction, and interpretation. The initial campaign, under the direction of Fiske Kimball and largely executed by Milton Grigg, involved the reconstruction of the west wing, which had fallen in. Internally the house received a Colonial Revival treatment with much white paint on the wood surfaces. Grigg and Kimball remained connected with work at Monticello for the rest of their lives, but in the 1960s and 1970s Floyd Johnson and Frederick Doveton Nichols became involved. Since the 1980s and 1990s John Messick has been the architect and William L. Beiswanger of the staff has been in charge of the restoration. In the 1980s Jefferson's original graining on the doors was restored. In the early 1990s a tin-shingled roof copying Jefferson's original was installed. In 1998 two shuttered verandas opening off his wing were reinstalled, altering the symmetry of the house. Internally much attention has been directed to Jefferson's original furnishing plan, and many of the furnishings are original.

Monticello was the main house of an extensive plantation and home to over 100 people, including slaves, who lived on the mountaintop. In the immediate vicinity of the house Jefferson tried a number of landscaping schemes over the years, in a series of different styles. The meandering path of the garden to the immediate southwest of the house indicates his interest in the English picturesque garden. In recent