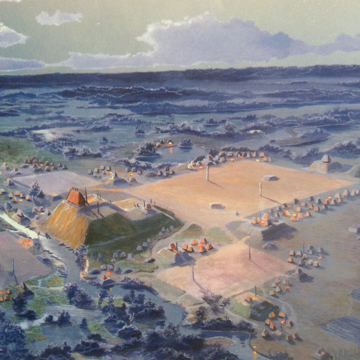

The Cahokia Mounds are located on the site of a pre-Columbian Native American city situated directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. An aerial view convinces us that Cahokia was laid out by people with remarkable design skills. With monumental presence, more than one hundred mounds rise from the earth, covering six square miles. At the center, four vast plazas honor the four cardinal directions; the largest extends forty acres, more than five times the size of St. Peter’s Square in Rome. The climax, a four-tiered pyramid (later called Monks Mound) covers fourteen acres and rises 100 feet into the sky, the tallest structure in the United States until 1867 and the third largest pyramid in the western hemisphere after Cholula and Téotihuacan in Mexico. Clearly built to serve a large population, especially on festival days, in 1050 Cahokia had a population larger than London.

Archaeologists have demonstrated how the alignments of the mounds with the cardinal directions show that Cahokia is a landscape cosmogram. Native American architecture often translates patterns in the sky into man-made patterns on the earth to create a sacred geography for ritual purposes. At Cahokia, this material manifestation of a belief system also served as a teaching device. Residents routely walked through this celestial microcosm. Quadrangles, aligned north (with a 5 degree offset), east, south, and west, traced a horizontal dimension echoing the cardinal directions, and the great verticality of Monks Mound embodied the connection between the lower world and the heavenly upper world with the ascending ramp, like a cosmic stairway, tying together earth, land, and sky.

Here, Native Americans, part of the larger Mississippian culture, altered a flat mud plain, transfiguring the given landscape into an exalted world. The site was chosen with great care. Four ecologies intertwined at Cahokia—forest, prairie, river valley, and hilltop. With waterways, grasslands, and forest all close at hand, fish, meat, fowl, grains, and building materials were bountiful and easily transported in baskets. In less than three hundred years they built a city with refined artistic expression and monumental architecture.

The mounds defy contemporary architectural analysis. Today they have no visible ornament. Each one is a solid that does not enclose space, although collectively they define and mark large plazas. The structural system is simply compressed soil. Separately each mound can be reduced to only one architectural element—mass—yet all the mounds together give proportion, scale, and scope to a human need to feel at once closer to the earth and at one with the universe. The emotions the ensemble evokes are profoundly architectural.

Building earth mounds requires enormous human effort. Scholars have calculated that making a structure as large as Monks Mound required carrying 14,666,666 baskets, each filled with 1.5 cubic feet of soil, weighing about 55 pounds each, for a total of 22 million cubic feet. An average pickup truck holds 96 cubic feet, so it would take 229,166 pickup loads to bring the same amount to the site. In addition to the mounds the Cahokians also built four palisades, five woodhenges, and many other structures. The creation of such a mammoth civic and sacred landscape was possible only because nearly everyone at Cahokia shared the same belief and the same vision. The religious, social, political, agricultural, and personal all found expression this work of landscape urbanism, which gave people’s existence structure, meaning, and a dimension of significance it would not otherwise have had. It has remained unrivaled in North America ever since.

No issue is thornier than the question of why Cahokia was abandoned, why it shows no sign of human habitation from 1400 to 1650. Various theories have been suggested: climate change, environmental stress, resource depletion, health and sanitation problems, armed conflict, or conscious abandonment to seek new options in a better land. But the story of Cahokia was not over in 1650.

In the late seventeenth century what happened at one moment in Europe could change the landscape in Cahokia a short time later. When a French Canadian visitor to Paris, Pierre Boucher, told Louis XIV of the richness of the territory to the south, the king launched a new effort to colonize it. French explorers mapped the region and by 1735 a small Christian chapel was erected on the first of the four great terraces on Monks Mound. Gradually British influence began to dominate the region, the French chapel fell apart, and the land around Cahokia languished until a bold new Virginian American, George Rogers Clark seized the British fort at nearby Kaskaskia and claimed it and the surrounding territory for the new state of Virginia. Shortly afterwards, two aspiring business men set up a “cantine” near the pyramid which lasted until about 1784. In 1809 a French Trappist monk arrived with about 80 tonsured cohorts to begin a consummate building enterprise—a monastic community called Notre Dame de Bon Secours, Our Lady of Good Hope. Although this effort was defeated by a series of diseases, financial and natural disasters, notably the infamous New Madrid earthquake of 1811–1812, they left the name “Monks Mound” as their legacy to the site and departed in 1813.

The modern period at Cahokia began in 1971 with the hiring of archaeologists William R. Iseminger and James Anderson as the first professionals to supervise the site. Working out of a former residence they oversaw the creation of exhibitions, acquisition of land, removal of vegetation, and gradually welcomed other archaeologists to the site until outside recognition was finally achieved. Managed as a state park since 1925, in the late 1970s Cahokia was reclassified as an Illinois State Historic Site and in 1982 it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Two years after the UNESCO designation the State of Illinois granted $6 million for the construction of a new Visitors Center at Cahokia and later added $2.6 million for exhibition costs. Architect Charles Morris gave the building a low profile so the gently sloping roof is like a subdued echo of the surrounding mounds. The shape of the mass, like an open boomerang, pulls visitors toward its earth-warm beige brick walls. Inside, are models, reconstructions, and interpretive materials that allow visitors to reconstruct in their imaginations the vibrant, booming, capital city that Cahokia once was.

Cahokia remains an awe-inspiring sight, one that resonated with the vastly different dreams of successive visitors for centuries after the Mississippians built it. At times the chords it struck were religious, at times commercial, agricultural, opportunistic, archaeological, or preservationist. Traces of the “cantine,” a farm house, an early railroad embankment, a drive-in movie theater, a housing development, and a small runway have been documented by generations of archaeologists, but nothing compares to the monumentality of the great pyramid, foregrounded by the plazas, and the subordinate mounds and other structures that transformed this landscape into a commanding urban form.

References

Chappell, Sally A. Kitt. Cahokia: Mirror of the Cosmos. University of Chicago Press, 2002.