Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unity Temple is a house of worship of monumental repose, rather than soaring aspiration. Wright abandoned the time-honored ecclesiastical metaphor of reaching heavenward for a gesture rooted in the Earth, a “natural building for natural Man,” as Wright wrote in his autobiography. Following a 1905 fire that burned the Oak Park Universalist Church, Pastor Rodney Johonnot hired parishioner Wright to design a new church that would emphasize the importance of worship in an intimate but capacious room, while also separating the worship space from more secular community functions. He was to do all this for just $40,000.

Building upon more than a decade of successful residential commissions that he used to developed and define the Prairie Style, Wright and his studio, which at the time included William Drummond, Barry Byrne, Walter Burley Griffin, and Marion Mahony, had just completed Buffalo’s Larkin Administration Building (1903), then his largest public work. In order to meet the tight budget, and building upon a previous commission for the Universal Portland Cement Company at the Buffalo Exposition (1901), Wright constructed the building from reinforced concrete, a relatively new material that was still then considered too industrial for architectural expression. While not the first reinforced concrete building, Unity Temple explored the material’s potential for dignified architectural expression decades before it became commonly used.

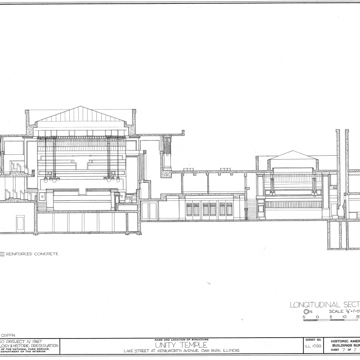

The composition of Unity Temple recalls that of the Larkin Building and anticipates the Guggenheim Museum. It has three sections: the Sanctuary and Unity House, which are connected by the enclosed breezeway. The Sanctuary rests at the prominent southeast corner of Lake Street and Kenilworth Avenue, just a few blocks east of downtown Oak Park. Narrow windows articulate the great corner masses while pilasters decorated with an abstracted leaf motif support the overhanging flat roof, bearing upon a high sill. The simple, seamless watertable, sills, and parapets communicate the plasticity inherent in the building’s reinforced concrete construction, while a varied aggregate finish brings depth and texture. At the south end of the lot, Unity House contains community functions (social gatherings, Sunday school, etc.). Shorter and rectangular in plan, Unity House is composed of the same lightly aggregated concrete surface as the Sanctuary. With its narrow end facing the street, it reads as a smaller version of the Sanctuary, and this interplay of square and rectangle becomes a motif throughout the building, in plan, section, and detail.

Steps along Kenilworth Avenue, obscured behind a high site wall, lead up to a small terrace. Walled on all three sides, the terrace quietly separates visitors from the busy street. Three sets of paired wood and art glass doors lead into the building, with the phrase “For the Worship of God and the Service of Man” set in bronze letters above the doors. Upon entering, doors on the left lead into the Sanctuary, a tightly interlocked space with three stories of balconies wrapping the nave on three sides, with the altar on the south wall. Upon entry at the cloister level, one can ascend a half story to the main nave space, or climb the stairs in the northern corners to the middle and upper balconies. The main space and stacked balconies provide space for 400 congregants, while still maintaining an easy intimacy. High windows and skylights with an art glass square-and-rectangle motif bathe the room in warm light, without the distractions of the busy surrounding streets. The smaller Unity House is similarly bathed in light filtered through art glass skylights.

At Unity Temple, Wright re-envisioned the blocky geometries, articulated masses and skylit isolation of the 1903 Larkin Building at a smaller and more intimate scale. While the Larkin Building possessed the monolithic uniformity associated with concrete construction, it was built of brick, with pink-tinted mortar. At Unity Temple, Wright felt free to exploit the new material in a way that would, perhaps, have been too daunting in a building of the Larkin’s size. Even at this smaller scale, however, the concrete at Unity Temple ultimately proved problematic. Without adequate expansion joints, cracks quickly developed in the surface of the concrete, opening the walls up to moisture penetration and the inevitable deterioration of the steel reinforcement within. In 1973, the exterior was coated with a layer of smooth concrete, obscuring the pebbled finish but providing the building with a watertight envelope. In the 1960s, the interior of the building was repainted in a delicate autumnal palette. In 2015–2017, the Unity Temple community began a thorough rehabilitation of the building to return the aggregate finish and historic interior colors, and to install new, energy-efficient building systems. Unity Temple remains in active use.

References

Brooks, H. Allen. The Prairie School. New York: W.W. Norton, 2006.

Cannon, Patrick F. Unity Temple: A Good Time Place. San Francisco: Pomegranate,

2009.

Uechi, Naomi Tanabe. Evolving Transcendentalism in Literature and Architecture:

Frank Furness, Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. Newcastle on Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013.

Secrest, Meryle. Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 1998.

Siry, Joesph M. Unity Temple: Frank Lloyd Wright and Architecture for Liberal Religion. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Wright, Frank Lloyd. An Autobiography. 1936. Reprint, New York: Horizon Press, 1977.