You are here

Yale University Art Gallery

The Yale University Art Gallery was first conceived when the artist John Trumbull donated his collection of American paintings to Yale College in 1832. With a small mausoleum-like building constructed to house the collection (long since demolished), Trumbull’s gift founded what would grow to become the most important university art collection in the United States. Today, the Yale University Art Gallery is comprised of three architecturally distinct buildings that are physically connected: Peter Bonnett Wight’s Street Hall of 1866, Egerton Swartwout’s Old Yale University Art Gallery (now Swartwout Hall) of 1928, and Louis Kahn’s building of 1953. The three structures were restored and expanded from 2003 to 2012 by Ennead Architects (formerly Polshek Partnership), which for the first time united the three buildings as a programmatic whole.

Situated along two separate blocks of Chapel Street in New Haven, the gallery faces the street from the north side at what is the southern edge of Yale’s main campus. Progressing in reverse chronological order with York Street to its left, Kahn’s Modernist building begins with a sunken courtyard, and then rises four stories above the street grade. The front facade—its most austere—is a wall of brown brick with limestone stringcourses that reference the slab concrete floors behind them. The building is set back slightly at its eastern edge to allow for access to a western-facing flight of steps that is the museum’s main entrance. The wall above the entrance, the York Street facade, and the building’s rear are composed of glass curtain walls, with thicker mullions along the floor edges.

The Egerton Swartwout building—to the right of Kahn’s and equal in height—was built in a Gothic Renaissance style inspired by Florentine buildings such as the Bargello. On the left is a large rectangular space, a tower rises in the middle, and an arched bridge crosses High Street and connects to Street Hall on the next block. The building’s facade is sandstone masonry, and the large rectangular block is fronted by five arched windows beneath decorative moldings and a cornice. The tower is set back and slightly taller, at street level there are arched windows and an entrance, a small balcony juts from the second-story, and on the third level, there is a band of narrow arch windows beneath corbels, false machicolations, and a narrow cornice. The bridge passage to Street Hall has a low arch for car traffic beneath narrow arched windows, a metal clock-face, and battlements on both sides. On the opposite side of the street there is a small tower with a lantern where Swartwout Hall connects physically to Street Hall.

Built in a Ruskinian Gothic style, Street Hall is the oldest of the gallery buildings and also the narrowest. The original plan was an asymmetrical “H” shape—three rectangular forms one in front of the other—but additional galleries were added to the northwest corner, and later concealed behind the High Street bridge. Facing the building on Chapel Street, the front-most of the three rectangular spaces is all that is visible. It is a two-and-a-half-story structure with a hipped roof and an off-center, projecting entrance (nearly equal in height to the rest of the structure) with a gable roof. Broken into bays, three to the left and one to the right of the entrance, the facade is organized into four sections, from bottom to top: unadorned basement windows, ground-floor pointed-arch windows, a quatrefoil design, and small triangular dormers. The entrance is raised several steps above grade with a pointed-arch vestibule supported by two small columns. It is beneath a pointed-arch window with a quatrefoil pattern. The facade is composed entirely of local brownstone except in the voussoirs of the arched windows, where brown- and cream-colored stones alternate, and on the roof where there are multicolored slate tiles below skylights of glass and steel.

In 1864, Augustus Russell Street, a New Haven native, proposed a School of Fine Arts for Yale, which would be the first of its kind in the United States. Street was inspired by the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, which he came to admire while living abroad with his family. The architect, Peter Bonnett Wight, had recently won the competition for the National Academy of Design in New York, and was chosen for his commitment to the Ruskinian Gothic style at a time when it was becoming the preferred expression on Yale’s campus. Conceived with a more elaborate exterior, including conical tops for the turrets, the design was scaled back after controversy arose with Street’s widow, who gave preference to interior ornamentation that Wight found to be gratuitous. Nonetheless, he stayed on to complete the project and continued to advocate for decades that his design be completed, although its appearance has never been altered. In the end, the interiors remained more modest than the exterior. The program included skylit galleries on the upper floors, and studios, offices, and lecture rooms on the first floor and basement level. The building was expanded in 1911 to address the university’s growing art collection.

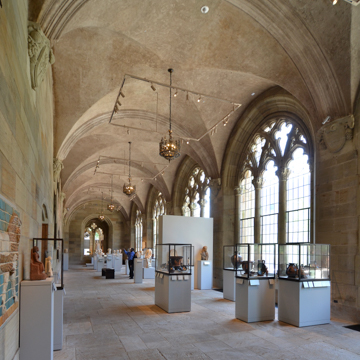

Although discussions began much earlier, expansion plans did not make haste until 1922, when the Dean of the School of Fine Arts, Everett Meeks, argued that the university collections were at risk in facilities without proper fireproofing. Furthermore, with galleries now repurposed as classrooms there was limited access to the collections. Egerton Swartwout was selected by James Gamble Rogers to design the new Art Gallery (although it would be renamed the Old Yale University Art Gallery upon completion of Kahn’s 1953 addition). Rogers was responsible for the university’s masterplan and the designs for many of Yale’s Collegiate Gothic buildings. Swartwout, who was trained in the Beaux-Arts tradition, struggled to design a Gothic building on such a scale required, which included new galleries, classrooms, offices, a lecture room, a library, and a stone bridge to connect to Street Hall. The latter would now be used exclusively for the study of studio art, architecture, and the history of art. Swartwout’s building was a synthesis of historic and modern-day construction: masonry walls carry the floor loads, but concrete slabs are used in place of stone arches (except in the mezzanine), with steel and glass employed for gallery skylights. The building was meant to be the first phase of development of a structure that was to include two large wings flanking a central hall. University spending was halted during the Great Depression, and when expansion plans resumed in the late 1930s, the original Swartwout design was seen as overly lavish.

Louis Kahn’s addition was conceived in January 1951, at the behest of George Howe, then the head of the university’s architecture program. With Yale’s history of constantly growing and exceeding its spatial constraints, a building that could be highly flexible was desired, but it was designed with the understanding that it would eventually be a museum exclusively. In aid to versatility, Kahn designed “pogo-stick” wall panels, with spring mechanisms and rubber feet, that were highly-portable and easily reconfigured. As non-essential construction was banned during the Korean War, the building was developed as “Design Laboratories and Exhibition Space,” explained by its brief use by the architecture school before a standalone building was completed.

Kahn’s building reflects the proportions of Swartwout’s 1928 structure, but in a decidedly Modernist style that made it the first of its kind on the campus. The building is one larger rectangle to the left of a smaller rectangle of the same proportions. The ceilings are reinforced concrete with a tetrahedron pattern of triangle shaped voids and pyramidal forms, a notable feature that allowed lights, vents, and wiring to be recessed and hidden unobtrusively. The building stairs and elevator shafts are located centrally in the larger of the two rectangles, allowing for the most economy on how the space would be used. The staircase is encased in a large concrete cylinder that exceeds the height of the top floor and culminates with a clerestory window that surrounds a triangular form that, in turn, mimics the triangular shape of the staircase below. Railings are metal and the openings beneath are covered with wire mesh. Floors are made of small oak strips, like a gymnasium, and black terrazzo is placed around the centrally located service area, the non-glass perimeter walls are 4 x 6–inch concrete bricks.

The Art Gallery was Kahn’s first major project and was the start of a masterful two decades of buildings, which concludes with the Yale Center for British Art, directly opposite the Gallery on Chapel Street.

In spite of an assault of structural changes during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, the university has made great efforts to restore integrity to Kahn’s vision. It was the first structure to be renovated and restored during a 2003–2012 renovation project by Ennead Architects, led by management partner Duncan Hazard and design partner Richard Olcott. Restorations to Kahn’s building concluded in 2006. Priorities were the upgrades to building systems and small programmatic changes, but mainly, repairing areas of neglect in attempt to restore and preserve as many original details as possible. The complete renovation, which concluded six years later, united Street Hall, Swartwout Hall, and the Kahn building as a unified whole for the first time. In the 1866 and 1928 buildings, interiors were restored to their periods of construction using extant historic details. A modern elevator shaft was added to the interior of Street Hall to better suit visitors, but improvements were otherwise mechanical, thermal, and systematic. Ennead added a small zinc- and glass-roofed pavilion to Swartwout Hall, which allowed for the incorporation of a new intimate sculpture terrace.

The Yale University Art Gallery has remained inventive throughout its history. It is a renowned art collection with an architectural heritage to match. Ruminating on exceptional museums, Ada Louise Huxtable opines, “when a museum and its contents come together as an integrated aesthetic whole...the art is enlarged and exalted, and the viewer’s rewards and responses are increased.” The interior spaces, constantly adapted to new functions, were largely spared from gut renovations or renewals, which fortunately allowed for them to be rejoined as a harmonious whole. It is the discontinuity between the structures, both their interiors and exteriors, and the way they are stitched together architecturally, that enhances both the museum’s collections and the visitor experience. Each structure uses the former as a point of departure, but their connectedness ensures harmony that might otherwise seem impossible. The building expresses the history of Yale’s campus, American tastes, and architectural ingenuity, all the while being a repository for objects that equal the buildings in their importance.

References

“Grand Opening Of Reinstalled Gallery Follows Multi-Year Renovation And Expansion Uniting Three Historic Buildings.” Yale University Art Gallery, December 2012.

Goldberger, Paul. "Yale's Architecture: A Walking Tour." New York Times, June 13, 1982.

Huxtable, Ada Louise. On Architecture: Collected Reflections on a Century of Change. New York: Walker and Company, 2008.

Kane, Patricia E. "Egerton Swartwout's Gallery of Fine Arts at Yale University." Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, 2000.

Matheson, Susan B., and Victoria J. Solan. "Street Hall: The Yale School of the Fine Arts." Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, 2000.

McCarter, Robert. Louis I. Kahn. London: Phaidon, 2005.

Newhouse, Victoria. Towards a New Museum. New York: Monacelli Press, 1998.

Ouroussoff, Nicolai. "Restoring Kahn’s Gallery, and Reclaiming a Corner of Architectural History, at Yale." New York Times, December 11, 2006.

Pinnell, Patrick. The Campus Guide: Yale University. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999.

Scully, Vincent. Louis I. Kahn. New York: George Braziller, 1962.

Scully, Vincent, and Neil Levine. "Louis I. Kahn and the Ruins of Rome." Modern Architecture and Other Essays. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Venturi, Robert. Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1966.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.